Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a disorder of neurology which affects the brain centers that control all the steps required to plan, focus on, and complete tasks with efficiency. Below, ADHD is broken down into 3 presentations: The “hyperactive”, the “inattentive”, and a combination of the previous two, which is called the “combined presentation.” Note: The word “presentation” is used because ADHD can show up at any point as one, two, or all three of these, dependent upon seen/unseen variables. Further is a brief exploration into the previously mentioned presentations, how the ADHD brain is different than that of the neurotypical/typical brain, how many people this disorder affects worldwide, and a few of the things ADHD is most certainly not.

What ADHD Is

The 3 Presentations of ADHD

According to The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, there are 3 presentations of ADHD:

Physically Hyperactive/Impulsive ADHD Presentation

Physically Hyperactive ADHD presents as someone “driven by a motor.” They generally exhibit almost no impulse control, tend to be impatient, usually need movement, and interrupt or talk when it’s not appropriate.

Below is the official DSM – V criteria for a diagnosis of a Hyperactive/Impulsive Presentation:

- At least 6 of these must have been present for the previous 6 months and be inappropriate for the patient’s developmental level.

- Persistent patterns of hyperactivity and impulsivity that interfere with daily functioning.

- Fidgeting with or tapping hands or feet frequently.

- Leaving one’s seat when remaining seated is expected.

- Running or climbing excessively in inappropriate situations.

- Being unable to play or engage in activities quietly.

- Talking excessively.

- Interrupting or intruding on others’ conversations or games.

- Having difficulty waiting one’s turn.

Inattentive ADHD (Formerly ADD) Presentation

Also considered mentally or intellectually hyperactive, people who are presenting this form of ADHD struggle with finishing tasks, following instructions, and focusing, are easily distracted and forgetful, and may be considered daydreamers who lose things often, and lose track of conversations.

Below is the official DSM – V criteria for diagnoses of an Inattentive presentation:

- Six or more symptoms of inattention for children up to age 16 years, or five or more for adolescents age 17 years and older and adults.

- Symptoms of inattention must have been present for at least 6 months and be inappropriate for the individual’s developmental level.

- Failing to give close attention to details or making careless mistakes in schoolwork, work, or other activities.

- Having trouble holding attention on tasks or play activities.

- Not seeming to listen when spoken to directly.

- Failing to follow through on instructions and not finishing schoolwork, chores, or duties.

- Struggling with organizing tasks and activities.

- Avoiding or disliking tasks that require sustained mental effort (e.g., schoolwork or homework).

- Losing necessary items for tasks and activities (e.g., school materials, keys, mobile phones).

Combined Type ADHD Presentation

As may be obvious, this is a combination of the above presentations. If someone presents 6 criteria for both Hyperactive and Inattentive ADHD presentation, this is considered the combined presentation.

Other considerations include

- ADHD must have been present in the patient before the age of 12

- Presentations cannot be better accounted for by other psychiatric disorders, and should not occur during a psychotic disorder.

- Symptoms must not solely result from oppositional behavior.

How is the ADHD Brain Different?

The ADHD brain comes standard with a developmental delay (3 years in children) of certain structures in the brain, primarily the Prefrontal Cortex, The Basal Ganglia, and the Limbic System.

The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC)

The prefrontal cortex is a part of the brain which is vital for thinking, making decisions, and controlling behavior. In individuals with ADHD, the PFC resembles a bustling intersection without traffic lights or stop signs, causing messages about attention, behavior, and emotions to collide chaotically. This disarray often results in the most dominant or quickest message taking precedence, leading to distractions and challenges in maintaining focus. For example, a person with ADHD might lose their original intent upon encountering an unrelated task, like spotting unfolded laundry when heading upstairs, causing a shift in focus. Additionally, ADHD affects the PFC’s role in time management and decision-making, making it difficult for those affected to plan, estimate time accurately, and make sound decisions.

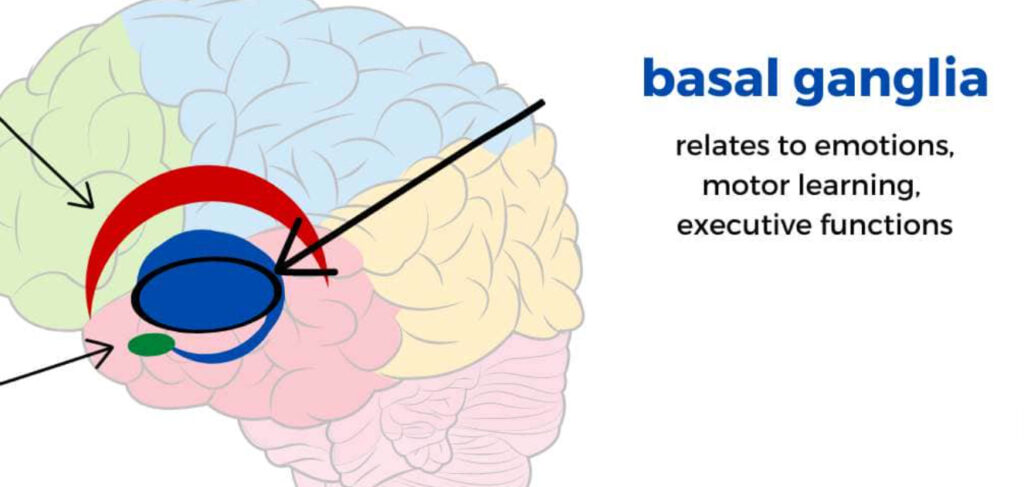

The Basal Ganglia

The basal ganglia is a group of structures deep inside the brain that plays a big role in learning new movements and controlling how we act, plan, and do several things at once. When someone has ADHD, this area of the brain doesn’t work as well, making it harder for them to pick up new skills through practice and to stay on top of their behavior.

A key part of the problem involves dopamine, a chemical that helps send messages in the brain and is linked to the basal ganglia. People with ADHD usually have lower levels of dopamine, which messes with their ability to pay attention, control impulses, and appreciate rewards. Think of the basal ganglia like a music conductor who can’t keep the orchestra in harmony because of this chemical imbalance.

There’s also something called the Default Mode Network (DMN), which is part of the brain that kicks in when we daydream or aren’t focused on anything particular. For people with ADHD, this network is on more than it should be, making it hard to stay focused on the task at hand. It’s like trying to listen to a radio station that keeps changing channels on its own, which makes keeping a steady focus a real challenge.

The Limbic System

ADHD, or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, greatly affects the limbic regions of the brain, which are crucial for our emotions and motivation. These areas act like the emotional control center of the brain. When someone has ADHD, this control center can become chaotic, leading to an emotional rollercoaster.

This chaos can manifest as hyperactivity, making it difficult to remain still or calm, and it can lead to inattention, making concentrating on tasks a real struggle. Additionally, people with ADHD might find making decisions harder due to these changes in the limbic regions.

The limbic system also acts as the brain’s reward system, helping us to feel pleasure when we accomplish something or enjoy an experience. In ADHD, this reward pathway doesn’t work as it should, making it seem glitchy and altering the way rewards and pleasure are perceived.

How Many People Does This Affect?

ADHD is an deeply misunderstood, unique disorder of the brain that affects about 5% of children and about 2.5% of adults, globally. Though most researchers and ADHD professionals believe these to be under-estimates due to a lack of proper reporting/knowledge on the subject.

All of the above has been thoroughly proven through the channels of rigorous clinical research and the use of brain imaging and neuroscience.

Other, equally important notes from this research include that ADHD is not a disorder of behavior, a mental illness, or a specific learning disability, though all the aforementioned can be comorbidities: or co-occurring symptoms/diagnoses.

What ADHD Is Not

- ADHD is not a lack of willpower, a character flaw, or a condition people ‘grow out of.’

- It is a complex disorder that requires understanding and proper management throughout a person’s life. In fact, attacking someone who has ADHD with statements like this will likely provide the opposite of the desired response, and even if you do get the response you’re going for, you’ve induced shame on a person who is doing their absolute best, all the time.

- ADHD is not a problem of motivation or laziness.

- People with ADHD often try very hard in all the areas life demands however, ADHD brain chemistry is generally low on dopamine and norepinephrine, which regulate motivation, attention, and reward. If you had a condition that lowered the very thing you need to muster up the motivation to write that paper, or the attention needed to read that book, or the simple experience of pleasure after doing a good job on anything, and had been experiencing this your entire life, how likely is it you would be able to do those things?

- ADHD is not a one-size-fits-all diagnosis. As noted above there are three types of ADHD. Each type has different symptoms and challenges. A common saying coming through conversations by experts on ADHD is that “if you’ve met one person with ADHD, you’ve met ONE PERSON with ADHD.” Every person has a different experience, and as ADHD proliferates all aspects of the lives of the people it affects, every presentation is slightly different.

- ADHD is not caused by bad parenting, poor diet, or too much screen time. Although these factors may affect the severity of the symptoms, they are not the root cause of the disorder. ADHD is a disorder that is based in the physiology of the brain, which is influenced by genetic and environmental factors. In fact, if a parent has ADHD, any of their children have 8 times the likelihood to also have it. If a child has ADHD, each parent has a 50% chance of also having it.

- ADHD is not a rare or new condition. It affects about 5% of children and 2.5% of adults worldwide. It has been recognized and documented for over 200 years.

As I’m a student of the sciences, and choose to value empirically proven evidence more than anything else, it seems most likely to me that ADHD is an evolutionary trait developed for some reason over the 65 million years it has taken for our ancestry to evolve into modern humans. However, if you’re not of the same mind, cool. Just don’t walk around acting like it doesn’t exist. In my experience, people who have typical brains sometimes struggle to see the possibility that different brains could exist.

When it comes down to it, it’s likely we still have a lot to learn about the brain, behavior, and how best to treat the real challenges they pose. What we currently know is that ADHD is an enigmatic neurodevelopmental disorder which exhibits three different presentations. We know the brain structures and populations that are known to be affected. We know that ADHD is not a lack of willpower, character flaw, or a condition people grow out of; it is not a problem of motivation or excess laziness; it is unique to each individual who has it; it isn’t caused by bad parenting, poor diet, or too much screen-time, and it’s not a rare or new condition. Stay tuned, this is one of 9 articles diving deeper and deeper into ADHD. Feel free to leave any questions. We look forward to hearing from you.

Would you rather have this weekly newsletter, chock-full of all things ADHD sent to you? You can! Please click this link Think Divergent Thursdays.

If you think ADHD is something you or someone you know struggles with, feel free to set up a consultation call where we can discuss the ins and outs of ADHD, how coaching could help you, and even if we can’t help, we’ll definitely work to set you up with someone who can.

References:

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Britannica. (2020). Primate. https://www.britannica.com/animal/primate-mammal

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). What is ADHD? https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html

- CHADD. (n.d.). Myths and misconceptions. https://chadd.org/for-adults/myths-and-misconceptions/

- Crichton, A. (1798). An inquiry into the nature and origin of mental derangement: Comprehending a concise system of the physiology and pathology of the human mind and a history of the passions and their effects (Vol. 1). T. Cadell, Jun. and W. Davies.

- Evans, B. (2017). Did Hippocrates know about ADHD? https://www.additudemag.com/did-hippocrates-know-about-adhd/

- Hoffmann, H. (1844). Der Struwwelpeter oder lustige Geschichten und drollige Bilder. Rütten & Loening.

- Hublin, J.-J., Ben-Ncer, A., Bailey, S. E., Freidline, S. E., Neubauer, S., Skinner, M. M., Bergmann, I., Le Cabec, A., Benazzi, S., Harvati, K., & Gunz, P. (2017). New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens. Nature, 546(7657), 289–292. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22336

- Kuhn, C. (2010). The history of ADHD – Part 1: Early references to ADHD-type behaviors. https://www.additudemag.com/the-history-of-adhd-part-1/

- Polanczyk, G., de Lima, M. S., Horta, B. L., Biederman, J., & Rohde, L. A. (2007). The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(6), 942–948. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942

- Schweitzer, J.B., Hanford, R.B. & Medoff, D.R. Working memory deficits in adults with ADHD: is there evidence for subtype differences?. Behav Brain Funct 2, 43 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-2-43

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. (n.d.-a). Hominini. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/species/hominini

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. (n.d.-b). What does it mean to be human? https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-family-tree

- Stringer, C. (2016). The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1698), 20150237. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0237